From A Brief Historical Description by Professor Sir John Baker QC LLD FBA

Master of the Bench

Who We Are

- The Inner Temple Today

- William Niblett - A Life Re-Examined

- History of The Inner Temple Video

- In Brief

- Pegasus Emblem

- The Archives

- Spoken History

- Admissions Database 1547-1940

- Bench Table Orders 1845-1945

- Calendars of Inner Temple Records 1505-1845

- The Christmas Accounts 1614-82

- Charles and Mary Lamb in the Inner Temple

- Grand Day

- Life in Halls: Designs of the Previous Incarnations of the Inner Temple Hall

- Gorboduc, or the Tragedy of Ferrex and Porrox

- Lord Robert Dudley, 'chief patron and defender' of the Inner Temple

- Lost in the Past : The Rediscovered Archives of Clifford's Inn

- Phoenix from the Ashes: The Post-War Reconstruction Of The Inner Temple

- The "Unfortunate Marriage" of Seretse Khama

- The admission of overseas students to the Inner Temple in the 19th century

- The Inns Of Court & Inns Of Chancery & their Records

- William Cowper of the Inner Temple

- Library Manuscripts

- The Freehold

- Paintings

- Silver

- Our People

- Work for Us

- Notable Members

Home › Who We Are › History › The Inner Temple History › The Knights Templar

The Knights Templar

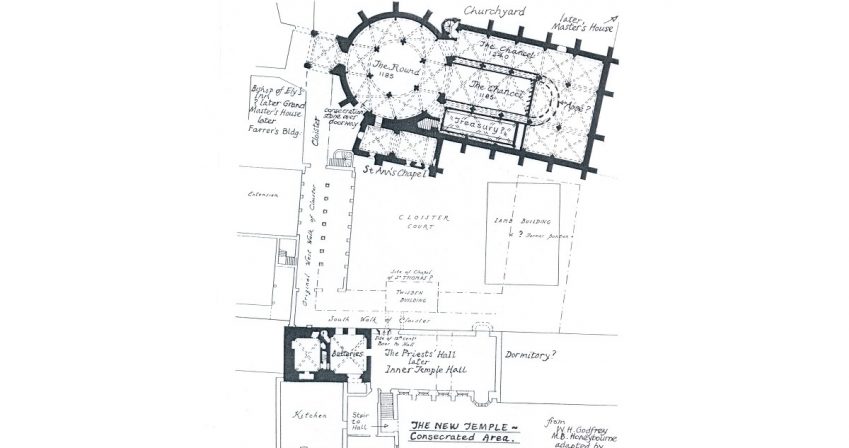

The history of the Temple begins soon after the middle of the twelfth century, when a contingent of knights of the Military Order of the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem moved from the Old Temple in Holborn (later Southampton House) to a larger site between Fleet Street and the banks of the River Thames. The new site originally included much of what is now Lincoln’s Inn, and the knights were probably responsible for establishing New Street (later Chancery Lane), which led from Holborn down to their new quarters. Following their custom, the knights built a round church patterned on the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. An inscription on the Round recorded that it was consecrated by the Patriarch Heraclius on 10 February 1185, in honour of the Blessed Virgin Mary. It is thought that King Henry II was also present on that day, inaugurating a long association between the royal family and the Temple.

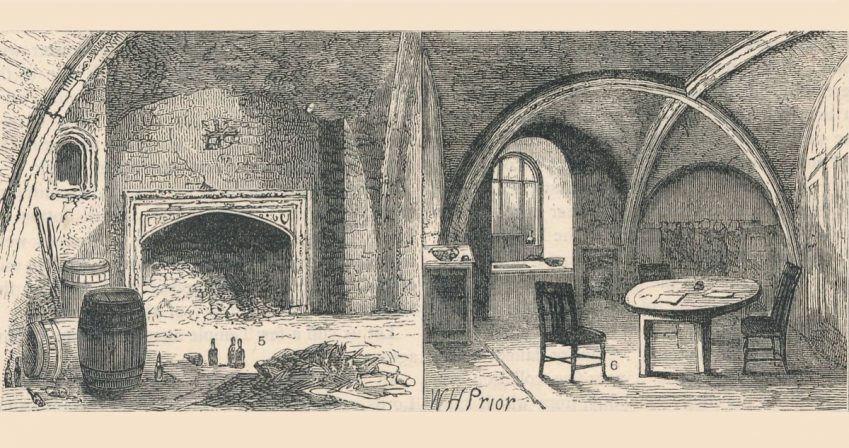

Inner Temple Old Buttery. Left: Fireplace in the Inner Temple; Right: Buttery of the Inner Temple

Plan of the Inn as it would have appeared at the time of the Knight’s Templar by W H Godfrey and M B Honeybourne

Among the other buildings erected by the knights were dormitories, storehouses, stables, chambers, and two dining halls, one of them in the consecrated central portion and connected with the church by a cloister. It was a house fit for kings to stay in, and several did so. During a visit by King John in January 1215 he received a deputation of barons demanding a charter of liberties; and when the Great Charter was signed later in the year, the Master of the Temple was one of the witnesses. The knights took advantage of their special privileges to make their sanctuary a safe place for depositing treasure, and during the thirteenth century the New Temple became a busy financial centre. It was no doubt during this period that the first handful of lawyers came to live in the Temple, not as distinct societies but as legal advisers to a wealthy international organisation. The Templars thrived, adding to their round church a fine nave, which was consecrated in the presence of King Henry III in 1240. Many knights associated with the order were buried in the church, the most distinguished being William Marshal (d. 1219), first Earl of Pembroke and regent of England, the very model of medieval English chivalry, and one of the instigators of Magna Carta. Marshal’s armoured effigy, battered by time and war, may still be seen in the Round.

South aisle of Temple Church from the round

After losing the Holy Land in the 1290s, the order of the Temple fell into a decline. The knights were dubiously accused of improprieties, and in 1312 their order was dissolved. Although the pope granted their estates to the Knights Hospitaller of St John of Jerusalem, King Edward II seized the New Temple as forfeit to the Crown. Nevertheless, the consecrated portion was conceded to the Hospitallers, and the remainder was sold to them later.