On the anniversary of the birth of Mahatma Gandhi, we look back to an earlier view of Gandhi’s life in London written in 1972 for The Pioneer, an English language daily newspaper in India.

Who We Are

- The Inner Temple Today

- William Niblett - A Life Re-Examined

- History of The Inner Temple Video

- In Brief

- Pegasus Emblem

- The Archives

- Spoken History

- Admissions Database 1547-1940

- Bench Table Orders 1845-1945

- Calendars of Inner Temple Records 1505-1845

- The Christmas Accounts 1614-82

- Charles and Mary Lamb in the Inner Temple

- Grand Day

- Life in Halls: Designs of the Previous Incarnations of the Inner Temple Hall

- Gorboduc, or the Tragedy of Ferrex and Porrox

- Lord Robert Dudley, 'chief patron and defender' of the Inner Temple

- Lost in the Past : The Rediscovered Archives of Clifford's Inn

- Phoenix from the Ashes: The Post-War Reconstruction Of The Inner Temple

- The "Unfortunate Marriage" of Seretse Khama

- The admission of overseas students to the Inner Temple in the 19th century

- The Inns Of Court & Inns Of Chancery & their Records

- William Cowper of the Inner Temple

- Library Manuscripts

- The Freehold

- Paintings

- Silver

- Our People

- Work for Us

- Notable Members

Home › Who We Are › History › Historical Articles › Gandhi and The Inner Temple

Gandhi and The Inner Temple

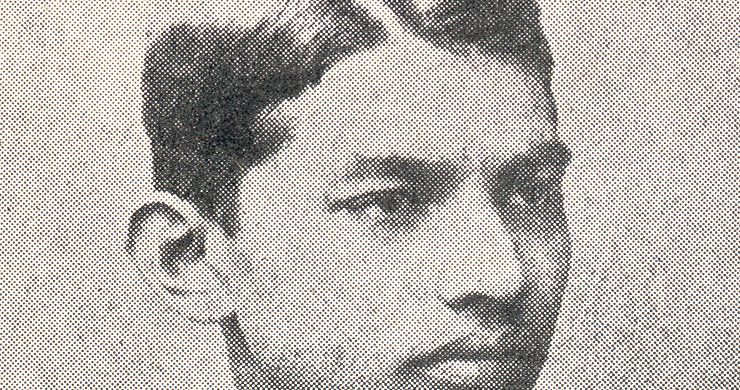

Mahatma Gandhi

The Pioneer, Monday 2 October 1972

IN SEARCH OF GANDHI’S LONDON

By John Williams

About this time of the year, booksellers and librarians notice that more people than usual ask for books on Mahatma Gandhi, and up and down the country commemorative meetings are being planned. It is all part of the build-up to the anniversary of Gandhi’s birthday on 2 October.

The planning of celebrations to mark the historic birthday remind one that Gandhi spent several of the most important years of his young life in London and the experiences he had here and the things he learned played a very important part in the moulding of the character that the rest of the world was to revere many years later.

It was in London that Gandhi gained his experience of the world outside India, rounded off his formal education with matriculation and achieved the legal world’s choicest accolade of being called to the Bar. He also took Western dancing lessons and studied the violin and tried to speak without an Indian accent.

It was here that he became a convinced vegetarian after reading the printed arguments and meeting the Western world’s pioneer vegetarians.

So, apart from following the arrangements made for the celebration meetings, I decided to go out and discover just how many of the places and buildings that Gandhi came to know well actually remain, such as the houses he lived in, and the buildings in which he studied, and so on, in the closing years of the last century.

The newest reminder of India’s famous son is the handsome wooden plaque donated by the Calcutta Art Society, which now graces a wall in the library at the Inner Temple, that seat of legal knowledge where Gandhi was admitted to the ranks of the lawyers.

Gandhi and the Inner Temple

0:00

-0:00

Gandhi left Bombay on 4 September 4 1888, in the steamer Clyde and disembarked in Britain seven weeks later after ‘celebrating’ his 19th birthday at sea. He was so shy on board ship that he spent most of the time in his cabin. He emerged at meal times but ate very little at table because he could not bring himself to ask which dishes did not contain meat. He would sit silently, waiting for the time to pass until he could seek refuge again in his cabin and assuage his hunger with the fruit and sweets he had brought from Bombay.

Gandhi was not then a convinced vegetarian and had only refrained from eating meat because of a promise extracted by his mother. This practice caused him acute embarrassment in London until he discovered that a growing number of English people were taking up vegetarianism.

At first it was not easy to avoid meat dishes, but Gandhi never succumbed to the mute temptations of English cuisine or the blandishments of less orthodox fellow Indians in London, several of whom were to become very impatient with Gandhi’s strict adherence to the tenets of his creed.

A surprising side-effect of his vegetarianism was that it later caused him to take lessons in elocution and ballroom dancing and to learn to play the violin.

Gandhi plaque unveiling

Once disembarked at Tilbury docks in the River Thames, Gandhi and his cabin companion Tryambakrani Mazumdar went by train to London where they booked into the Victoria Hotel. I found it impossible to trace which of the many ‘Victoria’ hotels he used. Even now, Gandhi could not bring himself to ask for a meal with no meat and he was still subsisting largely on the provisions he had brought from Bombay.

To conserve his funds, Gandhi soon moved out of the hotel and after a few weeks found himself living with the family of an Indian widow in the royal borough of Kensington. Here Gandhi was served with the right type of food but found it insipid and it did not satisfy him. But even among his own kind, the callow young man was too reticent to ask for more and again he left the meal table hungry. He was driven to writing home for supplies of sweets and other comestibles.

An example of how self-effacing the young Gandhi in London could be was afforded one evening when Palpatram Shukla, one of four Indians to whom Gandhi had letters of introduction, decided to give him a night out with dinner and a visit to the theatre. They sat down at a table in the Holborn restaurant, now out of existence, and when the soup was set down by the waiter, Gandhi timorously asked whether it was vegetable soup.

Inexplicably, this angered Shukla so much that he snapped at a bewildered Gandhi:

You are too clumsy for society. If you cannot behave yourself you had better go. Feed in some other restaurant and await me outside.

When Shukla had completed his meal, he went out and found a hungry Gandhi waiting for him. A nearby vegetarian restaurant at which he had tried to get a meal was closed for the evening.

Recalling the incident later, Gandhi observed:

I accompanied my friend to the theatre but he never said a word about the scene I had created.

Gandhi was later to discover several vegetarian restaurants where he could eat without embarrassment. In those days of Victorian England, vegetarianism was generally considered to be a cranky fad, although a movement of non-meat eaters had emerged.

Gandhi had come to London primarily to study law, but before he settled down to the serious work he applied himself diligently to keeping a promise he had made to Shukla. After the restaurant incident, Gandhi had assured his friend that

I would be clumsy no more but try to become polished and make up for my vegetarianism by cultivating other accomplishments which fit one for polite society. And for this purpose I undertook the all too impossible task of becoming an English gentleman.

He decided that the clothes he had brought from Bombay were of the wrong ‘cut’ for London, and so he went along to the Army and Navy Stores in Victoria Street, between Victoria railway station and the Houses of Parliament, to buy new ones. The Stores are still there, little changed from Gandhi’s day, and have recently celebrated their centenary.

I also went in for chimney pot hat costing 19 shillings – an excessive price in those days. Not content with this, I wasted pound 10 on an evening suit in Bond Street, the centre of fashionable London.

To give himself the correct bearing to go with his new clothes, Gandhi decided to take dancing lessons. That cost him three pounds for a term. He went along for two lessons each week but after three weeks realised that the smooth rhythms of Western ballroom dancing were beyond him. But if he could not dance, Gandhi thought he might be able to make music and so he enrolled for violin lessons. Again the initial fee was three pounds. Elocution lessons were also required, he thought, to suppress his lilting Indian pronunciation of English, and so another guinea was spent.

Fortunately, at this juncture, Gandhi regained his sense of proportion and realised that as he was only in England for three years there was no point in adapting his voice to English style, that dancing alone would not automatically transform him into an English gentleman, and that he could learn to play the violin in India.

The ‘infatuation’ had lasted for about three months, until he realised that

I was a student and ought to get on with my studies. I should qualify myself to join the Inns of Court.

Barrister Gandhi Takes the Stand

0:00

-0:00

But his attention to sartorial correctness persisted, and a perceptive description of the young Gandhi during his London student days was recorded by another Indian, Sachchidanand Sinha. Sinha came across Gandhi walking along through the crowds in Piccadilly Circus – the road junction known as ‘the hub of the Empire’ – in February 1890.

He was wearing a high silk top hat, burnished bright; a Gladestonian collar, stiff and starched; a rather flashy tie displaying almost all the colours of the rainbow, under which was a fine striped silk shirt. He wore a morning coat, a double-breasted vest [waistcoat], and dark striped trousers and not only patent leatherboots but spats over them. He carried leather gloves and a silver-mounted stick.

Sinha concluded that Gandhi was a student

more interested in the frivolities and fashion than in his studies

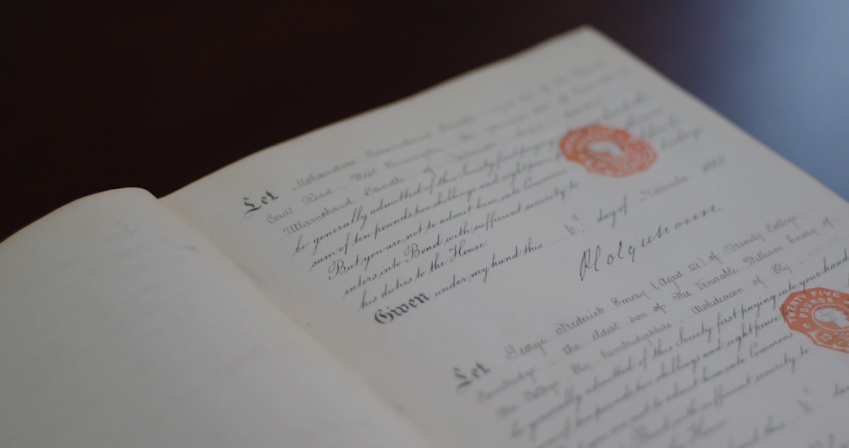

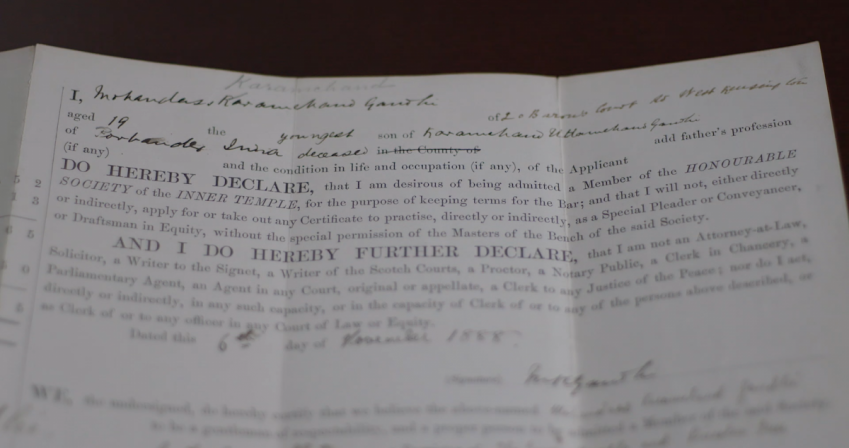

But there was another more serious side to Gandhi; he was admitted as a student of the Inner Temple on 6 November 1888. The forms that he completed in his strong, legible, handwriting and the books that he signed are still there. The admission book shows that he paid £140-1s-5d in fees on 6 November 1888.

To conserve his limited funds, he decided to give up his place with the widow and her family and to rent his own room. He selected an address that allowed him 30 minutes' walk to his studies.

It was mainly this habit of long walks that kept me practically free from illness throughout my stay in England and gave me a fairly strong body,

he recalled.

The young law student started cooking his own breakfast of porridge and cocoa and at night he dined on bread and cocoa. Anyone seeing him dressed up could never have suspected that he lived so frugally.

Actually, he managed to reduce his expenses to only one shilling and three pence a day and rejoiced that he was not being such a drain on his brother in India who was sending him money.

He eventually came across a vegetarian restaurant in Farringdon Street – which is at one end of Fleet Street not far from St Paul’s Cathedral. He was overjoyed at its discovery, and it was here that Gandhi was at last converted to a true belief in vegetarianism.

There is no indication now of where in the street the restaurant was situated because so much rebuilding has taken place. As he entered it, Gandhi saw a selection of books for sale in the doorway. Among them was Henry Salt’s treatise A Plea for Vegetarianism, published by the Vegetarian Society, which had been launched in Manchester.

Buy a copy for a shilling. Gandhi read it avidly and was to declare:

From the day of reading this book I may claim to have become a vegetarian by choice.

Gandhi became quite prominent in the Vegetarian Society, being elected to the London committee in September 1890, going along to their meeting in the Memorial Hall, Farringdon Street, and contributing articles to their journal.

The Vegetarian Society, now at a different address, allowed me to look through their old minute books and I soon found the relevant entry. Among the record of the Society’s meeting on 19 September 1890 was the ink-written item

It was resolved to invite [and seven names were listed including ‘Mr M K Gandhi’] ...to sit on the committee

The last reference to Gandhi in the minutes was to record his presence at the committee meeting of 5 June 1891, shortly before he returned home.

It was Gandhi’s practice to go and live in a different part of London about every six months to familiarise himself with as much of the capital as possible, and while living in Bayswater he formed his own vegetarian club. Unfortunately, it foundered when he moved away, perhaps because he could not be replaced as secretary with a sufficiently zealous organiser.

Because Gandhi liked to change his address so often, it is difficult to trace the houses in which he lived in London over 80 years ago, but I did manage to locate two addresses with the help of the secretariat at the Inner Temple.

One was 20 Barons Court Road, in West Kensington. This was obviously then a proud middle-class residential road, where the long terraces of substantial houses had imposing porticos.

Now most of the houses have been split into self-contained flats whose residents have a cosmopolitan flavour. No one seemed to be aware that one of the world’s greatest men had ever lived there.

Another address was 15 St Charles’s Square in the Ladbroke Grove district, also on the west side of London. This seems to have been slightly lower down the social scale than Barons Court Road, but still well-to-do and quite respectable. Now, however, the houses show clear signs of neglect, with crumbling stonework and curtains not all clean. Again, there was no local knowledge of Gandhi’s former occupation.

He found that the studies needed to attempt the legal examinations were not too demanding and he had no difficulty in passing. He was called to the Bar – the ceremony in the dining hall of the Inn of Court at which successful students are presented with their certificates and are thereafter allowed to practise law – on 10 June 1891 and was enrolled at the High Court on the next day. He sailed for home the day after that.

It is not possible now to go and sit in the ancient library or the panelled dining hall in which the young Gandhi embarked on his legal career because they were bombed out of existence in 1940 during World War II. But the other buildings comprising the Inner Temple, which has been situated there between Fleet Street and the River Thames for 600 years, still survive as in his day, as does the magnificent wrought iron gate leading into the gardens where he would have gone to relax.

The new dining hall and library were opened by the Queen in 1952.

Confirmation of Gandhi's admission to the Inn

Gandhi's application for membership of The Inner Temple

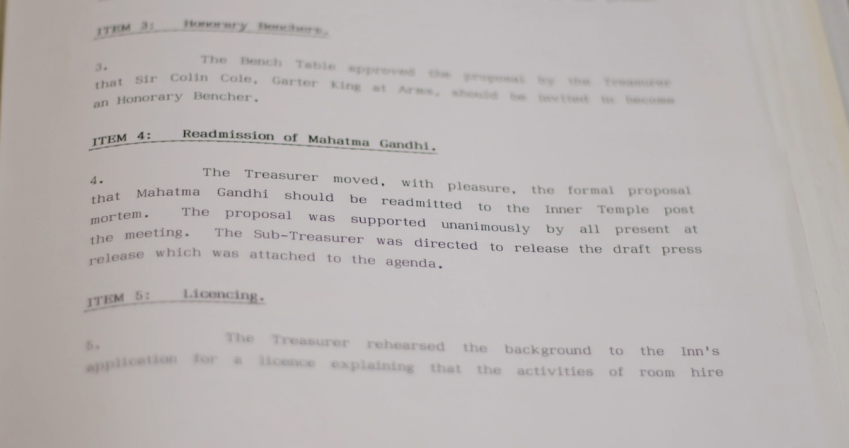

Bench Table minute of 3 November 1988 approving Gandhi's readmission to the Inn

And so, after three years in London, during which time he met many people involved with the Vegetarian Society, and went along to meetings of Indian university students here, the young Gandhi sailed away.

He was to return later, of course, as a very effective spokesman for the Indian people.

After his first visit, however, and because he was so inhibitingly shy that on several occasions he had stood up to make a public speech and then had to sit down again without being able to utter more than a jumble of words, Gandhi probably left behind an impression of a nice enough chap, but one unlikely to set the world on fire.

The Vegetarian, journal of the society, recorded kindly in its report of a farewell dinner at the Holborn restaurant – now unidentifiable – on 11 June 1891, that its executive committee member, Mr M K Gandhi, made “a very graceful, though somewhat nervous, speech”.

Gandhi’s own recollection of the occasion was more devastating.

My last effort at public speaking in England was on the eve of my departure for home. When my turn for speaking came, I stood up to make a speech. I had with great care thought out one which would consist of a very few sentences. But I could not proceed beyond the first sentence. I had read of Addison that he began his maiden speech in the House of Commons, repeating ‘I conceive’ three times, and when he could proceed no further, a wag stood up and said, ‘The gentleman conceived thrice but brought forth nothing.’ I had thought of making a humorous speech taking this anecdote as the text. I therefore began with it and stuck there. My memory entirely failed me and in attempting a humorous speech I made myself ridiculous. ‘I thank you, gentlemen, for having kindly responded to my invitation’, I said abruptly, and sat down.

Later, of course, both friends and acquaintances have revised their opinion of him, for Gandhi did indeed set the sub-continent on fire – figuratively...

John Williams

Courtesy of The PioneerGandhi's Readmission

By the Sub-Treasurer

Gandhi’s time in London prepared him for the road ahead and there are those who suggest that his legal and advocacy skills training enabled him to negotiate Indian independence proficiently and without a major war.

On 7 November 1922, Gandhi was sentenced at Ahmedabad to six years’ imprisonment (he was in fact released after two years) upon his plea of guilty to three counts of seditiously inciting disaffection towards the Imperial Government. As with any member of the Inn convicted of a criminal offence, following his conviction, he was ordered to be disbarred at a meeting of the Bench Table, on 10 November 1922. He never sought readmission during his lifetime.

In 1969, Lord Mountbatten, the chairman of the committee formed to mark the centenary of Gandhi’s birth, wrote to the Inn to suggest that readmission might be a fitting gesture, and to advise that the Calcutta Arts Society had offered the Inn a commemorative plaque. Bench Table declined readmission, doubting at that time whether it could be done posthumously, but had accepted the Gandhi plaque, which was unveiled in May 1971 in the presence of the Indian High Commissioner, Lord Elwyn-Jones and Lord Denning.

At a Bench Table on 3 November 1988, the then-Treasurer, Master Monier-Williams, a supporter of Gandhi’s readmission since his student days in 1949, moved with unanimous support that Gandhi be readmitted posthumously to the Inner Temple.