This article is not the first to analyse the life of William Charles Niblett (‘WCN’). Previous publications have by design been condensed to essentials, leaving many unanswered questions. Some of these questions will continue their journey into perpetuity and remain unanswered, but further research allows the majority to be addressed. Accordingly, it is now appropriate to provide a more detailed reflection of a complex individual.

Who We Are

- The Inner Temple Today

- William Niblett - A Life Re-Examined

- History of The Inner Temple Video

- In Brief

- Pegasus Emblem

- The Archives

- Spoken History

- Admissions Database 1547-1940

- Bench Table Orders 1845-1945

- Calendars of Inner Temple Records 1505-1845

- The Christmas Accounts 1614-82

- Charles and Mary Lamb in the Inner Temple

- Grand Day

- Life in Halls: Designs of the Previous Incarnations of the Inner Temple Hall

- Gorboduc, or the Tragedy of Ferrex and Porrox

- Lord Robert Dudley, 'chief patron and defender' of the Inner Temple

- Lost in the Past : The Rediscovered Archives of Clifford's Inn

- Phoenix from the Ashes: The Post-War Reconstruction Of The Inner Temple

- The "Unfortunate Marriage" of Seretse Khama

- The admission of overseas students to the Inner Temple in the 19th century

- The Inns Of Court & Inns Of Chancery & their Records

- William Cowper of the Inner Temple

- Library Manuscripts

- The Freehold

- Paintings

- Silver

- Our People

- Work for Us

- Notable Members

Home › Who We Are › History › William Niblett – A Life Re-Examined

William Charles Niblett - A Life Re-Examined

Well travelled, frequently enigmatic and often unfathomable, WCN presents a beguiling picture. Predictably the passage of time tends to dull precision and erase memories, but by contrast imagination never fades. The world would be a poorer place without imagination. Accordingly the reader is invited to employ rational imagination and reasonable inference to fill the remaining voids in this small history.

A plaque to WCN’s memory is to be found on the South side of Church Court, within the Inner Temple. It provides all that is needed by way of introduction.

Niblett Plaque (Credit: TMI)

There is another preliminary matter which requires emphasis. As this story unfolds it will become apparent that a fair and balanced assessment of WCN's life can only be achieved by appreciating the historical background and applying the elementary principle that persons are best judged against the customs and mores of the times in which they live. This observation is all the more significant since much of this story evolves around British Colonial Rule in the period 1850-1920, especially the development of Singapore, the ravages of the First World War and a changing social order. A robust approach will pay handsome dividends.

The Early Years

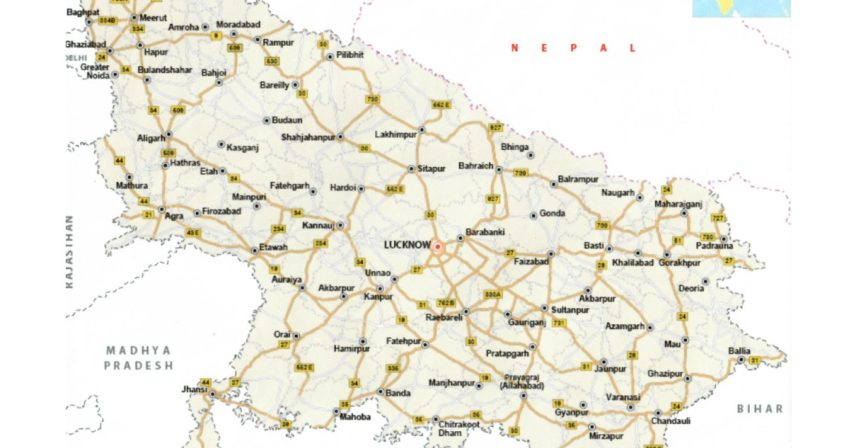

WCN was born in 1851 at Azamgarh, Uttar Pradesh, Northern India to Philip and Margaret Niblett. The Nibletts were a large and influential family (with many extended branches) who enjoyed a privileged life style. Philip Niblett held the post of Deputy Collector and sat as a Magistrate at Varanasi, then more usually known as Benares. He died in 1892.

The function of a Deputy Collector was one of considerable responsibility, the holder being a State service officer in charge of collecting revenue and administering a sub-district. Both duties encompassed the maintenance of law and order.

As regards distances, Azamgarh to Varanasi is approximately 61 miles, Azamgarh to Lucknow approximately 155 miles.

Map of Uttar Pradesh

Close examination reveals a discrepancy in WCN’s date of birth— the plaque refers to 1856, a date replicated in a number of documents of varying significance. However, the date of 1851 is also to be found, especially in more formal records such as his Certificate of Baptism, documents for admittance to the Inner Temple, and Bar lists. Further, a sequencing of the dates of birth of his 11 siblings - 7 brothers and 4 sisters-provides limited corroboration of the earlier date. All in all the better view points to 1851.

Surprisingly, there is no known photograph of WCN, but a hint as to his appearance can be gleaned from a description recorded in mid Oct 1911, taken from the passenger manifest of the Chiyo Maru, a passenger liner bound for England. It reads’ 5’11”, Fair complexion, White hair, Brown eyes’.

Two of his sisters, Henrietta (born in 1852) and Ellen (born in 1862) remained spinsters. They died within a day of each other in late May 1935 at Benares, the cause of death in each case being recorded as Heat Apoplexy. It was perhaps inevitable that WCN would loose touch with many of his siblings, but he was always careful—as touched on later—to ensure that the two sisters were financially secure.

Little is known as to his upbringing, other than loose family lore to the effect that he was a problem child, always in trouble, and was required to leave home.

With this in mind it is material to appreciate that the entire Niblett family endured considerable suffering during the Indian Mutiny.

During this period (1857-1858) British authority was perilously close to becoming extinct in the Bengal Presidency. Lucknow, Cawnpore, Allahabad, and Meerut were geographically close to Azamgarh. All these cities and their environs were the subject of violent rioting, widespread looting and killing, to be met with equally brutal reprisals.

The family were obliged to leave their home in Azamgarh, living in harsh and insanitary conditions, on occasion negotiating sewers and hiding in ravines to avoid stray musket shots being fired aimlessly overhead. The Niblett home was looted in their absence and papers destroyed, but Azamgarh itself was spared massacre.

WCN was 6-7 years old at the time. It can only be conjecture as to whether he was affected by these events, but the possibility is not to be rejected out of hand especially as two of his brothers died. George, aged two, succumbed to privations occasioned by the Mutiny, and James Edward, who was born in 1857 during the family’s exile from Azamgarh, was to die but two years later.

The family's tribulations have been carefully documented by Robin Niblett, bringing home the reality of and brutality of the times.

Family Record of Indian Mutiny

Education and Call to the Bar

Following his primary schooling, WCN attended La Martiniere College in Lucknow, joining in 1864 at the age of 13. How he fared is a closed book.

Nothing further is known as to his activities on leaving the College until 1879. Early that year, now aged 28, he travelled to England, enrolling as a student member of the Inner Temple on the 8th April. The 1881 census shows him to be single, resident at 1, Temple Gardens, sharing with 4 other law students. A year later, in May 1882, he was called to the Bar.

Yet again there is dearth of data following his call. Information as to whether he joined a set of Chambers, and if so his pupil master(s) and any preferred area of practice is wholly lacking. Looking at the chronology, it seems unlikely that he entered practice in England and Wales, although there is a hint that he may have done so briefly in Nigeria.

The only firm facts to emerge at this early stage of his career are that within a year or so of of his call he not only travelled to Cape Coast Castle (The Gold Coast) but also married. Quite why The Gold Coast was his choice of destination remains unresolved, but conjecture suggests it may have been a joint marital decision, influenced by his Swedish wife Bertha Maria, also referred to as Bertha or Berta Marie.

Early/Mid 1880's. WCN's First Marriage

On 18 October 1882 The Stockholm’s Dagblad carried a short announcement that WCN and Bertha Maria Osterberg were married on the 7 October 1882, aged 31 and 26 respectively. Where and how they met remains a mystery, as does the reaction of their respective parents. There are many indicators that the Osterbergs, in common with the Niblett’s, were a family of some note, their activities attracting a measure of public/social interest.

The wording of the announcement implied that the ceremony had taken place in London, but many years later, in the course of an early Court hearing relating to WCN’s bigamous 1917 marriage to Alice Deveson, it was suggested that the venue was Stockholm. In the event little turns on this discrepancy, but obtaining the formal record of marriage has proved elusive.

Cape Coast Castle and the Gold Coast. (Now Ghana)

Cape Coast Castle began as a trade lodge constructed by the Portuguese in 1555 on a part of the Gold Coast later known as Cape Coast. A number of competing European powers were well aware of its potential, but many preferred a policy of wait and see. This observation did not however apply to Sweden.

Following Sweden’s ousting of the Portuguese, the Swedish Africa Company built a permanent wooden fortress to further the already lucrative trade in timber and gold.

Swedish dominance was not to last—a decade later the Danes seized power, reconstructing the fort in stone. As with the Swedes, Danish participation was comparatively brief, losing control to Britain in 1664. Cape Coast became increasingly used for the developing slave trade, activities coming to a peak during the course of the 18th Century.

By 1700 the fort was transformed to serve as the Headquarters of the British Colonial Governor and remained in British hands. After the abolition of the slave trade if became an educational and administrative centre.

The precise date of WCN’s arrival at Cape Coast Castle is unknown, but it was almost certainly after his marriage in late 1882. Details of his day to day life are not recorded. The extent to which he concerned himself with legal and Court matters is also sparse, but there is ample evidence to demonstrate that he made his mark through a variety of disparate activities.

By good fortune a Swedish newspaper, The Gotlands Tidning, published a short report which provides a limited but nonetheless revealing insight into WCN’s activities.

Dated 9 August 1884 it covered WCN’s arrival in Stockholm from Cape Coast Castle, noting that he was accompanied by his Swedish wife Berta Marie.

The report went on to observe that WCN was not only a Barrister at Law from West Africa, but also a judge appointed by the English Government in Cape Coast Castle. It has not been possible to ascertain the accuracy of this latter assertion (or his judicial rank) but the reference to West Africa sits comfortably with the family lore that he had earlier practiced law in Nigeria.

The newspaper report continued,

He has now undertaken a recreational trip to Europe and Sweden, and spends the month of August in Visby. Mrs Niblett has in a foreign land preserved her warm love for the motherland and as proof of this she brought home some ethnographic objects, those she collected on the Golden Pillow (sic), as well as a collection of birds, which were later donated to the National Museum’s Zoological Department. Some of the ethnographic objects have been received for the National Museum’s ethnographic collection and another part for the Anthropological and Geographical Society is to be incorporated in this Society’s collection.

It seems that WCN was not to be outdone in the gift department. He too brought back cultural items on his return to Sweden. In September 1884 the Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography recorded that WCN had donated a number of cultural items, exampled by chairs, carvings and ceremonial knives, made by the Ashanti, Mandingo and Fante peoples.

WCN’s return to Sweden was short lived. He stayed for a month or two, returning to the Gold Coast to resume his legal practice.

Towards the end of the year he appeared before Lesingham Batley C.J., in the case of Davis v Jones, reported in Fanti Customary Laws, 18 December 1884. The case turned on the need to prove special damage where slander is alleged. Both parties were represented, WCN appearing on behalf of the defendant, a Mr Renner for the plaintiff.

The Court was singularly unimpressed with the forensic ability and professional ethics of Mr Renner. Delivering judgement, the C.J. observed

...there has not been a tittle of evidence to show that special damage has been suffered by the plaintiff. In such cases I cannot help remarking that it would be far more decorous if gentlemen of the Bar were to abstain from appearing in support of actions which they know are not maintainable for a moment.

The C.J., whose sensibilities and patience had clearly been tested, concluded “I observe that various cases were cited by the counsel for the plaintiff in the cause before the District Commissioner, apparently with a view of imposing on his want of knowledge of the law.”

It will come as no surprise to learn that appeal was allowed, with costs. The comment as to the District Commissioner’s lack of knowledge of the law was not a mere aside- it was very much a political barb. The Colonial authorities were well aware that a legal qualification was in practice regarded as an unfulfilled requirement rather than a necessity, suitably qualified applicants being somewhat thin on the ground.

The following year WCN continued to practice but also turned his hand to journalism, launching a monthly newspaper entitled The Gold Coast News, published in Cape Coast Castle. Unhappily the venture was not a success, lasting but a few months from 21 March to 20 August 1885.

The tone of the paper was described by Magnus Sampson in his book A Brief History of Gold Coast Journalism ‘as being very much in line with a contemporary publication - The Western Echo- providing fearless and unremitting criticism relating to popular concerns, especially on subjects such as banking and the Court system.’

WCN’s venture into publishing is also note worthy in that it represented a further indication of his leaning towards commerce. This was a characteristic that had manifested itself immediately following his Call to the Bar, and was to gain increasing traction as his career developed.

The Late 1880s

WCN returned to England in the late 1880s. At this juncture he came into contact with an agent for the Sultan of Johore, who recommended that he serve the Rajah in the capacity of Barrister. Further details remain elusive, but the offer, although seemingly not accepted with immediacy, was undoubtedly a factor that led to his arrival in Singapore.

The Sultan, Abu Bakar al-Khalil, reigned from 1886-1895. He sought to maintain independence from Britain, encouraging economic development in Johore at a time when the majority of South East Asian States were being incorporated into European colonial empires. It will also be remembered that the Straits Settlements, comprising Singapore, Penang and Malacca, were transferred from the control of the Indian Government to that of the Secretary of State for the Colonies on 1 April 1867.

No further detail has come to light regarding WCN’s relationship with the Sultan’s agent, or indeed the precise implications of ‘serving the Rajah’. In truth, it may have been a florid turn of phrase that meant little more than an encouragement to join the Singapore Bar.

However, before travelling to Singapore was to become a reality it was apparent that other difficulties were emerging—-recent commercial ventures carried out by WCN in England had also failed, and were accompanied by damaging proceedings in the Bankruptcy Court, which in turn had entered the public domain.

Bankruptcy Proceedings, 1890

On the 25 June 1890 WCN was the subject of a Receiving Order, No 788 of 1890. The Gazette notice, listed as a creditors petition, read as follows.

“William Charles Niblett, lately residing at 42 Upper Bedford Place, London, and 53 Guildford Street, London, now residing at 9 Bristol Gardens, Maida Vale, London and carrying on business at 57-58 Chancery Lane, Barrister at Law, house and estate agents clerk.” The extent of debt is not recorded.

The Receiving Order raises more questions than it answers. There is no evidence that 57-58 Chancery Lane was ever home to any sets(s) of Chambers or Solicitors offices. However, an entry in the 1891 edition of Kelly’s Commercial Directory is of direct and obvious significance, listing the firm of Niblett and Co, estate agents, 57 and 58 Chancery Lane. It appears that WCN was trading on his own with potentially unlimited liability. Although this first foray into property was unsuccessful, it will be seen that the outcome of his later property dealing in Singapore had a very different outcome.

A cursory search demonstrates the diverse nature of tenants based at 57-58 Chancery Lane. Over the years , the premises housed such enterprises as Auction offices (1893), Advance and Discount lending firms (1885), and The International Institute of Technical Bibliography (1910), to say nothing of The British Oil and Turpentine Corporation.(1926). It also served as a Post Restante address for a Mr G. R. Buckland of the Surrey Bicycle Club. (1893).

Regretfully the events which led to the Receiving Order remain opaque, as does the question as whether the Receiving Order was ever discharged. However its ramifications were soon to come to prominence.

Ramifications of the Receiving Order

Notwithstanding the uncertainty over the discharge, the Order played a central role in two closely linked Court cases that were decided in 1890/1891. The cases revolved around a house at 42, Upper Bedford Place, a known previous address of WCN and mentioned in the Bankruptcy Notice.

Under the terms of an agreement dated 19 September 1888 the house at No 42, (stated to belong to WCN) together with its furniture and effects, was to be let to a Mrs Hoare for 12 months, with an option for Mrs Hoare to buy the furniture and effects after the expiration of her tenancy.

In the event WCN breached the contract, resulting in Mrs Hoare being denied her tenancy. She sued WCN for damages, the case being heard at Clerkenwell County Court. The Court awarded her £30 (now equivalent to c.£4100) damages and costs, but WCN’s bankruptcy prevented him satisfying the entirety of the sum due.

Mrs Hoare, undeterred, commenced a second action, this time against Berta Marie. This was a comparatively rare course, suggesting that WCN’s wife was considered to be wealthy in her own right. The case was again heard at Clerkenwell County Court.

Mrs Hoare was non-suited at first instance, but appealed. On the facts the Court of Appeal held that even if Berta Marie was to be regarded as a joint contractor with WCN, the ordinary rule applied, namely a judgement against one joint contractor (even though unsatisfied) was a bar to a subsequent action for the same breach against the other joint contractor.

It is of course a moot point whether the Receiving Order influenced WCN’s later arrival in Singapore. It was hardly unknown for those who perceived there was, or might be, a blot on their copy book to turn to the Colonies.

The 1891 Census

The 1891 census shows WCN to be living at Portsdown Road, Paddington (later renamed Randolph Avenue) with his wife Berta Marie and her unmarried sister Jennie.

His occupation is listed as Barrister. It is improbable that that he was then practicing. Not only was it difficult to find Chambers, briefs were far from plentiful, and Bankruptcy was an impediment in its own right. Quite apart from these matters, the litigation with Mrs Hoare would have presented further difficulties. It comes as little surprise to find that in October 1891 he left for Singapore.

The passenger manifest shows WCN, aged 40, occupation lawyer, travelling with a Lydia Niblett, aged 41. No occupation was given for Lydia, whose inclusion invites further enquiry. The question is, who is this particular Lydia Niblett?

There are at least eight Lydia Nibletts whose background qualifies them as possible candidates, many from the wider Niblett family based in Gloucestershire. The three most likely were born in c.1853, c.1860, and 1860, being the respective wives of George Niblett, Charles H Niblett, and Thomas C. Niblett.

From the facts available there seems no reason why any of these Lydia Nibletts—or indeed any other Lydia Niblett—should be travelling to Singapore. The census and electoral rolls are silent as to any such travel.

The answer may lie in the suggestion that the reference to Lydia was a sham, it being rather more likely that it was a front for Berta Marie. Although superficially attractive and redolent with intrigue, there is a difficulty with this interpretation, since at face value its rationale is not easy to understand. None the less, the sequence of events that was shortly to unfold provides a degree of credence to the suggestion, making it difficult to dismiss out of hand.

Singapore

The following year, in January 1892, within weeks of his arrival in Singapore, WCN was admitted as an Advocate and Solicitor of the Supreme Court of the Straits Settlements.

Later that year, as was customary for those in his position, he became a Mason. He was initiated into the Zetland in the East Lodge, thus continuing his membership which commenced in 1881 with the Urban Lodge, Clerkenwell.

Death of Berta Maria

As predicated above, the travels of WCN and the whereabouts of Berta Marie throughout 1892 and early 1893 are uncertain, but a degree of precision is provided by a newspaper report detailing the trial of the Niblett’s head house-boy in August 1893. He was charged with stealing as a servant —an aggravated form of theft— on the 19 May 1893, the property being itemised as a quantity of jewellery and English coins. The theft was first noticed by Mrs Niblett, who came across a number of discarded items in the kitchen. She promptly notified WCN, who in turn summoned the police.

A reward of 100 SGD was made available for the recovery of the property. Subsequent events reinforced the age old dictum that there is no honour amongst thieves, the house boy and his wife being subject to early arrest.

There was overwhelming evidence against the house-boy, leading to conviction and two years rigorous imprisonment. His wife, said to be complicit by way of receiving the property, was acquitted.

On 9 October 1893 a further degree of precision emerges. The Straits Times carried a notice that Mr and Mrs Niblett were staying at Raffles Hotel, Singapore, no mention being made as to any indisposition or impediment of health.

It is also known that within a matter of weeks both had made their way to India.

At this remove one can never be certain as the reason or reasons that prompted this journey, but whatever the cause there is a wealth of evidence to suggest that a sense of urgency prevailed. As events unfolded, it is reasonable to conclude that the urgency arose over Berta Marie’s physical health. It is not known whether this manifestation was sudden or had developed over time.

An advertisement in the Straits Times in late October 1893 speaks of an auction of various items of WCN’s personal property, followed by a further advertisement on 6 December reading

“ To be let with immediate entry. That commodious house situated in Orchard Road, No 89, lately occupied by Mr Niblett. Rent modest...”

The sense of urgency proved to be ominous and well founded, since tragedy was shortly to strike.

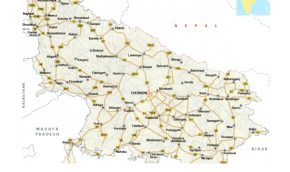

Nothing is known as to their movements in India. Where they stayed or who they saw is lost to time. Sadly, Berta Marie was to die on 10 February 1894, aged just 38.There were no children of the marriage and none of her relatives are recorded as being present at her death.

The cause of death was given as ‘Synscope due to Pulmonary Haemorrhage’. (sic). She was buried in the General Episcopal Cemetery, Calcutta. The photograph of her gravestone tells its own story.

Gravestone of Berta Maria Niblett. Calcutta

Return to Singapore. Resumption of Work. A Carriage Accident

Following the death of Berta Marie, WCN returned to Singapore resuming his law practice and developing his property interests.

Both these activities underwent a temporary interruption. In mid July 1895, early in the evening, a horse and carriage driven by a Mr and Landsmann was proceeding along the seaside Esplanade. Without warning the horse, startled by a passing rickshaw, reared and broke free of the carriage shafts, galloping unencumbered along the grass border of the road.

By a quirk of fate WCN was walking on the same stretch, his back to the horse. He was knocked down, badly winded and in pain. On arrival at Hospital he was found to be free of serious injury, but suffering shock and a compound fracture of his third left toe. He was expected to stay in the hospital for a week, but the exact length of his stay is not known.

Despite all, his legal practice continued to gather momentum, which over time had every appearance of being busy and varied. Besides acting for others he also found himself suing and being sued, giving rise to the perception that he was not averse to becoming personally embroiled in litigation.

A number of his cases were reported in the press, his representation of clients covering both criminal and civil matters of significance, including Murder, Fraud and Bankruptcy.

It has to be said that there were isolated instances (some examples follow) that did not reflect particularly well on WCN in his professional capacity. These occurred both before and after the death of Berta Marie.

In 1893 an order was sought that WCN be committed for contempt. It was alleged that he had threatened and technically assaulted a law clerk (by the throwing of papers at the clerk) in circumstances where the clerk was attempting to serve a summons in respect of a civil suit in which WCN was said to be acting. The case was dismissed as the evidence of assault was equivocal, and the correct procedure relating to service had not been followed. Nonetheless, the Court went on to deprecate the fact that WCN had written a letter in the course of the dispute couched in terms that ‘Gentlemen of the Bar should not write to each other.’

In 1897 WCN successfully appealed a fine of 1000 SGD imposed in respect of damages for wrongful re-entry as lessor of a number of houses in Sago Street. The fine was reduced to 100 SGD, the Court finding WCN’s conduct to have been neither harsh nor oppressive.

A happier result came about in November 1898. WCN sued a horse trainer for 765 SGD, on the basis that two horses sold to WCN were not, as had been asserted, ‘sound and quiet.’ WCN won his case, with costs. (For the avoidance of doubt, no disciplinary overtones arose in this case).

A further disciplinary incident arose in 1901, WCN having changed the wording on a notice which purported to threaten the institution of criminal proceedings. The reality was that the notice was designed to threaten the institution of legal proceedings, and was so printed. WCN admitted crossing out ‘legal’ and substituting ‘criminal’, accepting that his actions ‘were not strictly right’ The Court was less than impressed. However, having considered the factual background, it was content to issue a reprimand. No more was heard of the matter.

In 1907 Kong Soon, a builder, sued WCN for 2900 SGD for repair work done to WCN’s houses in Sago Street Lane. The houses had become insanitary and were subject to a Municipal order that repairs be occasioned. Judgement was given for Soon. (Again, no disciplinary issue arose in this case. The issue was whether WCN’s agent had abused his authority. The Court held he had not).

A final incident occurred in 1913, towards the very end of WCN’s career. It concerned the negligent drafting of a lease in his office, resulting in an Order to pay 3000 SGD in damages and costs of the action. It is unclear as to the degree of responsibility-if any- that attached to WCN in his personal capacity. It is to be remembered that his eye sight has been failing for some time, others worked for him, and he was unlikely to have been be involved in day to day drafting.

As already remarked upon, these occasional breaches of professional discipline do not reflect particularly well on WCN, but the fact remains that on any view they were minimal in terms of turpitude and a far cry from allegations of dishonesty or behaviour that might attract disbarment. Perhaps, to borrow an observation from a probation report written in another context in respect of a person unknown, WCN was a little too enthusiastic when approaching life’s obstacles.

The Wealth of WCN

As is well known, by the time of his retirement (c 1911, perhaps earlier), WCN had acquired great wealth. Although a reasonably successful lawyer, by no stretch of the imagination did his fortune reflect the fruits of his practice. His wealth was secured by another route, namely by investing in property, both freehold and leasehold. In this regard he was business like and shrewd. Operating very much on his own, he amassed a formidable portfolio.

The nature of the property holdings is discussed below. It has generated questions turning on standards, ethics and morality, on occasion coupled with a perceived need for censure. Understandably, reactions have varied in intensity, adverse comment gaining a limited degree of momentum over the passing years. This is hardly surprising given the awakening of society’s broader responsibilities to protect the vulnerable, promote public health and eradicate poverty. Nonetheless, as pointed out at the commencement of this article, we are all to be judged by the standards of the time and place in which we live.

Before examining WCN’s property portfolio, which in turn necessitates a review of prostitution in Singapore, it is appropriate to pause and take stock of WCN’s position as at his retirement. Possessed of great wealth, he was also widowed, childless, becoming blind and in failing health. It is realistic to suggest that he feared loneliness in the coming years. Quite apart from this bleak prognosis there is the clearest inference that Singapore had lost its attraction, coupled with a realisation that the time had come to divest himself of his riches. With the latter task in mind, he determined to travel to London and contact the Benchers of the Inner Temple, the Inn’s governing body.

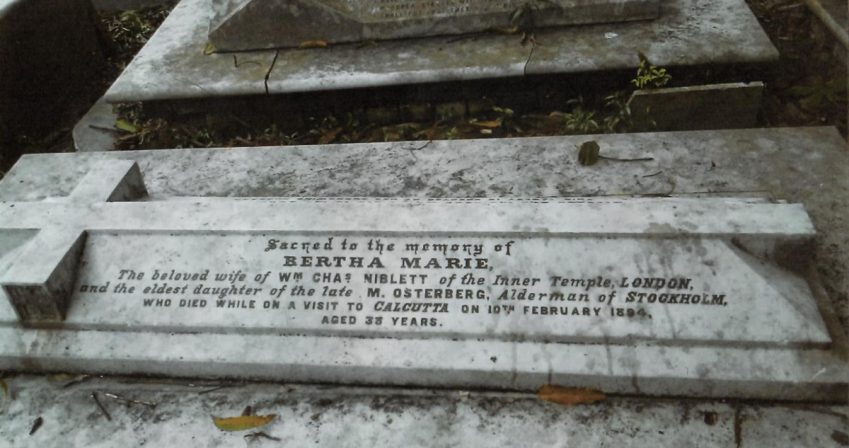

Prostitution in Singapore

When Stamford Raffles founded modern Singapore as a British trading settlement in 1819 there was a veritable flood of migrants from China, India and Malaya. Males heavily outnumbered females— by 1860 the population was some 81,000, the ratio being in the order of 14:1 This imbalance resulted in prostitution becoming a flourishing business and by extension brothels reaped the benefits. It is estimated that 80% of the women and girls coming from China to Singapore in the late 1870’s were sold into prostitution. Many lives were ruined, working in damp and dingy conditions, often suffering abuse and open to the ravages of disease.

The wooing of male migrant workers and entrepreneurs was deemed a necessity for the economic development of the Colony by the authorities, this approach remaining in place for many decades.

Further, the procuring of Asian females and bringing them to the Colony to serve male sexual desire was regarded by the public as normal and acceptable. Singapore was not alone in this regard— Georgetown, Batavia, Surabaya and other cosmopolitan centres in Southeast Asia were rife with prostitutes and brothels.

By 1877 there were 212 brothels In Singapore, the number rising to 353 in 1905.

This increase lent credence to the proposition that prostitution was viewed by the Colonial authorities as a necessary evil. However, the oft used phrase ‘Tolerated Houses’ - an obvious and well understood synonym for brothels- lessened the impact of the harsh realities, speaking volumes as to the concept of reluctant acceptance.

The principle of containment and control held sway for many years, it being argued that an outright ban would be counter productive. It would drive the trade underground, encourage yet greater exploitation, and allow venereal and other diseases, already a huge and worrying problem, to run unchecked.

A number of steps were taken to place restrictions on prostitution in the city. The registration of prostitutes and brothels was made compulsory in an attempt to prevent forced prostitution, and an Office to Protect Virtue was set up to help those unwillingly involved in prostitution.

Shortly after the outbreak of World War I the Colonial authorities banned prostitution by white women and as a result the white brothels in Singapore (over 20 in 1914) had all closed by 1916.

A 1916 report, amongst other matters, described the misery and plight of the prostitutes working in the red light districts around Malay Street and Smith Street. Pressure was placed on the Colonial Office in Britain to further restrict licensed prostitution.

Despite all, Sir Arthur Young, Governor-General of the Straits Settlements, remained wedded to history, arguing that prostitution was indispensable for the Colony’s economy and labour supply. Fortunately a more measured response prevailed, the sale of women and girls into prostitution being banned in 1917.

Between 1815 and 1918 well known locations for Brothels included:

Smith Street. Temple Street.

Sago Street. Trengganu Street.

Japanese Street. Amoy Street.

Banda Street. Upper Holkien Street.

Chin Hin Street. Duxton Road.

Neil Road. Pagoda Street.

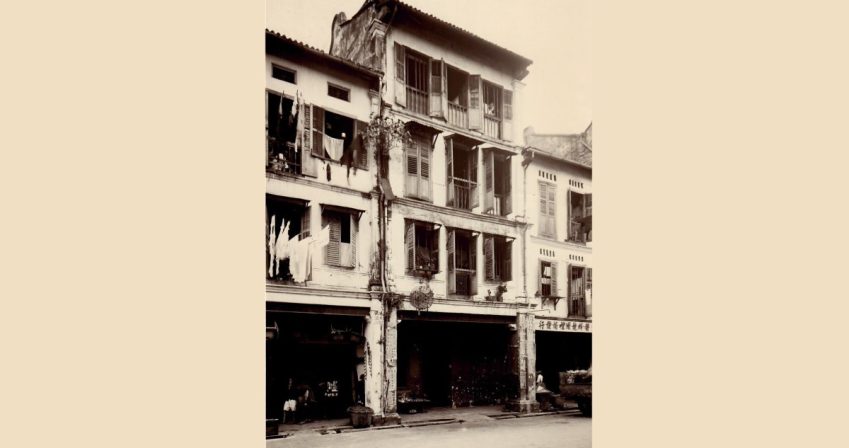

Smith Street was especially notorious, described as being lined with some 25 three and four storey shop-houses packed with prostitutes.

THE NATURE OF WCN’s PROPERTY PORTFOLIO

WCN had an interest in some 31 houses, all in Singapore. Asked to elaborate during one of his visits to the Inn, he explained that “3 were European dwelling houses outside the City, the remainder being in the City but occupied by natives and all were house-shops”.

WCN’s property holdings were to be found in the following locations.

26 leasehold houses in Sago Street/Sago Lane

3 Freehold houses in Chancery Lane.

1 Freehold house in Kampong Java Road

I Freehold house in Neil Road

Chancery Lane

MARRIAGE TO JESSIE WINIFRED TACON. A VISIT TO THE INNER TEMPLE

Following his return to England WCN, now in his early 60s and in far from robust health, married Jessie Winfred Tacon. The wedding took place at Honor Oak, in Oct 1912. The available material suggests this was primarily a marriage of convenience from the view of both parties.

WCN was already known to the Tacon family, there being evidence that he and Jessie’s father, a hosier and outfitter, were already acquainted. The nature and extent of the acquaintanceship remains obscure.

The Tacon family lived in Forest Hill, South East London. The 1911 census records Jessie, aged 38, as living at home and working in the capacity of bookkeeper.

Before her marriage Jessie’s mental health had been precarious, necessitating admission to Camberwell House Asylum. It seems that WCN was unaware of this matter, but following the marriage the spectre of her mental condition was to resurface with a vengeance.

WCN and his new bride travelled extensively, ultimately reaching Singapore in late May 1913. Despite this extended honeymoon It was apparent from her letters home that she was singularly unhappy and matters were not on an even keel.

An article written on 13 July 1913 in the Straits Times provides an interesting —and potentially significant— backdrop which has the capacity to shed light on later events.

It recorded that a brown leather bag containing a quantity of jewellery and other items valued at £160 belonging to Mr and Mrs Niblett, staying at Raffles Hotel, had been stolen from Borneo wharf. Also stolen were passenger tickets for two persons travelling from Singapore to London. A reward of 100 SGD was offered for the bag’s return.

There is no direct evidence as what affect this incident had (if any) on Jessie Niblett, or indeed as to her immediate reaction. Nor does history record whether any claimant stepped forward to claim the reward.

Rather more importantly, shortly afterwards Jessie Niblett returned to England, travelling alone. She was closely followed by WCN.

On her arrival home Jessie spoke to her father, alleging that when in Singapore WCN had resumed relations with a former mistress, causing her much distress. It was further implied by the family that the association had also caused a relapse in Jessie’s mental health, leading to her readmission to the asylum at Camberwell House. Given the overall frailty of Jessie’s mental heath it is quite impossible to assess fairly the veracity of this allegation, but there remains a perfectly realistic alternative explanation, namely that the trauma of the theft of her personal items triggered the relapse. This reasoning is given additional weight when one considers an unsigned note found in the Inn’s archives. Written on 9 July 1914, it read:

Treasurer’s Office.

I had an interview with Mr W.C. Niblett today, he informed me that he was not anxious to benefit his wife’s relations for the following reasons. Before his marriage he was assured by his wife’s father that the lady was in every way healthy and fitted to be his wife. 6 months after marriage she became insane, and Mr Niblett then discovered that she had been shut up in the same asylum in which she now is, for insanity before the marriage. The father, on being confronted with this, stated that he thought she was cured and there was no reason to tell Mr Niblett.

Sadly, Jessie Tacon never really recovered her full mental health, but nonetheless lived till 1960.

VISITS TO THE INNER TEMPLE. PROPOSALS BY WCN. THE BUILDING OF NIBLETT HALL.

WCN made his initial visit to the Inn in February 1914, augmented by the 9th July visit, and further visits in 1915. All had the principal aim of refining the terms of a proposed legacy in the Inn’s favour. He provided details as to the locations of his holdings in Singapore, including the legal and/or beneficial interest he held in each. At a later stage detailed accounts were also provided, showing the rental income and market value of each property. He pointed out that although he had no children, his immediate objective was to make provision for his wife Jessie and his two spinster sisters. That done, he would then consider his anticipated bequest to the Inn.

Arrangements concerning the welfare of his three relatives were executed without delay, reflecting considerable generosity to the beneficiaries.

WCN then proceeded to leave all his remaining property in Singapore to the Inn, subject to a lifetime personal pension of £800 per annum. He did so “out of allegiance to and affection for the Inn which called me to the Bar”. He requested that the money be used to build a lecture and examination hall, or in the alternative for any other purpose the Inn might think fit, stipulating that “my name of Niblett to be permanently associated with the building or object.”

The following year saw the Inn’s grateful acceptance, after which the rent revenues from the Singapore properties were received under trust for the Inn and Mrs Niblett.(‘The Niblett Fund’).

By the time of WCN’s death in 1920 the Niblett Fund amounted to some £18,000, worth well in excess of £1m at current valuations. The fund was further augmented by the sale of some of the properties.

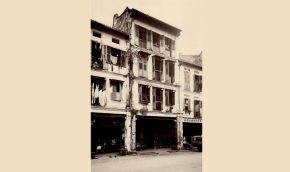

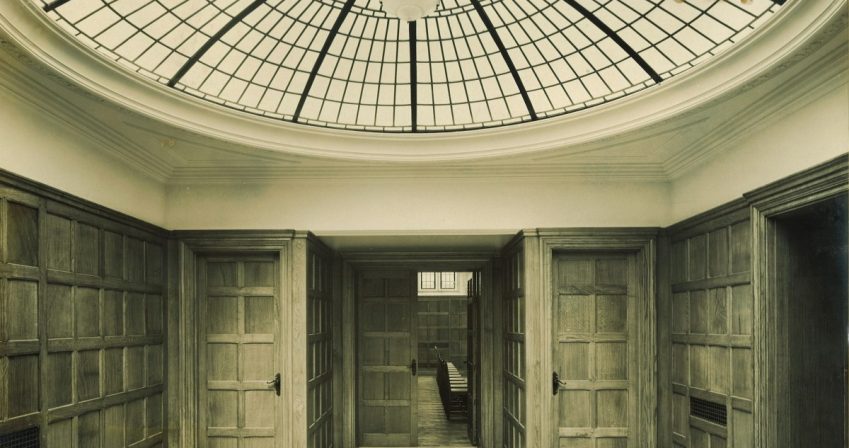

9 years later, following extensive discussions, the Inn took the decision to build what was to become Niblett Hall. True to WCN’s wishes, the Hall contained two lecture rooms and a meeting room for student members of the Inn. Built to high specifications it was formally opened in 1932.

Niblett Hall Vestible, 1932

Niblett Hall, 1932

A further project funded by WCN’s largesse was a scheme set up in 1939, offering financial assistance to chambers affected by members’ war service and to the Inn’s staff on military service in World War II. It was a much appreciated charity.

In the 1940s and 1950s Niblett Hall served as the Inn’s only corporate building, The Great Hall, Benchers Rooms, The Bar Common Room and The Treasury Office all being subject to rebuilding following war damage.

The Inn continued to draw income from the Singapore rents until the 1950s, by which time the remaining properties were in disrepair. In 1956, following advice from agents in Singapore, the remaining properties were sold.

By 1992 Niblett Hall was underused and little appreciated— it had been overtaken by new methods of study, alternative and better equipped meeting places were available and the quest for further space to house new chambers was ever pressing. It had served its purpose well, but the Inn was obliged to react to current conditions. In reality demolition was inevitable. That same year Niblett Hall met its fate, to be replaced by Littleton Chambers.

All that physically remains is the Pegasus carving, but it is comforting to know that members of the Niblett family were present at the unveiling ceremony of the commemorative plaque on Church Court. It is also fitting that the spirit of WCN, the carving and the story of his legacy continue to be gazed upon, absorbed and appreciated by members of the Inn.

THE FALL FROM GRACE. A BIGAMOUS MARRIAGE.

Following his disastrous marriage to Jessie Tacon and its distressing aftermath, WCN chose to base himself on the south coast, doubtless fearful for the future. In November 1917, at Kingston, Surrey, he married Alice Deveson, a widow sympathetic to his circumstances. He had met her in Brighton, she being said to be of ‘superior position.’ The marriage certificate showed him to be a widower, a clear and deliberate misrepresentation.

The marriage was again born of of convenience, WCN now having an increasing need to find a nurse/companion.

In early 1919, consequent upon a complaint lodged by Jessie Tacon’s father, criminal proceedings were instituted. When served with a summons alleging bigamy, he replied ‘Yes, I married this woman, my wife has been in an asylum for a number of years, what was I to do?’ It was a pertinent rhetorical question— the underlying problem was that marriage was legally barred to him, and the Devison family were unlikely to sanction co- habitation.

Inevitably, he was committed for trial at the Surrey Assizes.

THE SURREY SUMMER ASSIZES SITTING AT GUILDFORD.

On 26 June 1918, before Mr Justice Avory, WCN pleaded guilty to a single Count of Bigamy. He was represented by Sir Edward Marshall Hall, K.C., a fashionable and formidable advocate. The opening address and plea in mitigation are set out below and require no further elaboration. See pages 1-2 (Opening Address), pages 2-5 (Mitigation) and page 6 (Sentence).

Opening Address, Plea in Mitigation and Sentence

THE SENTENCE

The sentence imposed was a month’s immediate imprisonment. On its face this was surprisingly lenient, but the sentencing remarks reflect a compassionate approach, fully cognisant of the defendant’s plight. The demands of retribution and punishment were not paramount.

Reference was made to WCN’s substantial donations (£5000 apiece) to two London hospitals, but by contrast neither defending counsel nor Avory J.—both Benchers of the Inner Temple— made any direct mention of WCN’s largesse to the Inn, the reference by counsel being confined to ‘An institution’. A rather different approach would be taken today with regard to disclosure, but the fact remains that the sentence was appropriate and just, a primary function of any criminal court. See page 6 (Sentence).

DEATH OF WCN

There are differing details concerning the precise date of death. The probate notice refers to 30 April 1920, whereas Press reports mention the 2nd May 1920. In the event, nothing turns on this discrepancy.

An inquest was held on the 4th May 1920, returning a verdict of accidental death. Evidence was led that WCN attempted to board a moving bus at Holborn, only to slip and be crushed between the wheels and kerb.

His effects were recorded as £1193-4-9.

WCN was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery at the Inn’s expense. His grave can still be seen there today, restored to a fitting standard at the instance of Allan Gay Niblett, a close relative.

Gravestone of WCN. Kensal Green Cemetery

CONCLUSION

On any view WCN led a full and varied life. Notwithstanding early commercial setbacks and the occasional professional hiccup, he found his metier in Singapore, building a strong legal practice whilst simultaneously accumulating a massive property portfolio. Put another way, he was seemingly able to achieve his ambitions, often an elusive goal which is not open to all of us.

His life was also tinged with periods of melancholy. Berta Marie died at far too young an age, he contracted a disastrous late second marriage, and towards the end, dogged by general ill health and increasingly failing eyesight, compounded matters by committing bigamy.

His life spanned an age where values, mores and aspirations were very different. As with all of us he certainly had his faults, but on final analysis his notional account ledger comprising all his charcteristics, was far from one sided — generosity and a fully implemented wish to help others tells us much about a man, and in his case the reader may conclude that in all the circumstances he reached the end of his life with an intact credit balance.

Master Victor Temple, 2022

Acknowledgements:

I am grateful for assistance from Master Baker, Celia Pilkington, Henrietta Amodio, Kate Peters, Andrew Behan of London Remembers, Allan Niblett, Ranen Niblett, John Niblett and other members of the Niblett family.