Public lecture for the First Women Lawyers series, More House, 25 January 2019

Dr Mari Takayanagi, Parliamentary ArchivesWomen in Law

- Introduction

- Timeline

- Joyce Bamford-Addo

- Marion Billson

- Jill Black

- Elizabeth Butler-Sloss

- Eugenia Charles

- Lynda Clark

- Freda Corbet

- Coomee Rustom Dantra

- Leeona Dorrian

- Heather Hallett

- Frene Ginwala

- Rosalyn Higgins

- Daw Phar Hmee

- Lim Beng Hong

- Dorothy Knight Dix

- Sara Lawson

- Elizabeth Lane

- Theodora Llewelyn Davies

- Gladys Ramsarran

- Lucy See

- Evelyn Sharp

- Victoria Sharp

- Ingrid Simler

- Teo Soon Kim

- Ivy Williams

- The Significance of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919

- Podcasts

Home › Women in Law › The Significance of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919

The Significance of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919

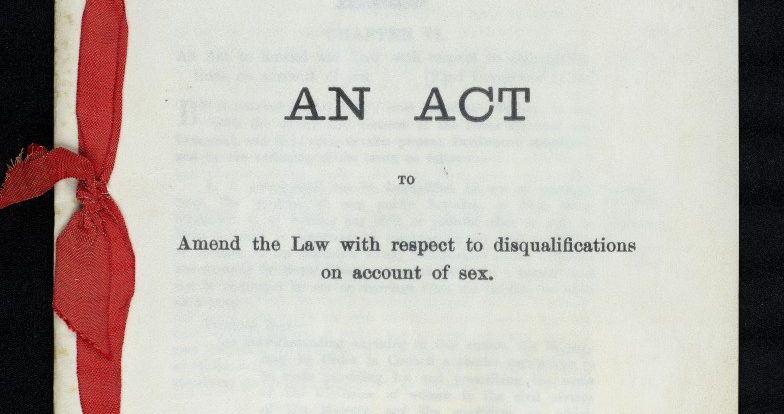

Cover of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919. (C)Parliamentary Archives

In 1938, Virginia Woolf wrote of ‘the sacred year 1919,’ in her essay ‘Three Guineas’. For people not familiar with it, it is an essay addressing the question ‘How can we prevent war?’ She sends a guinea each to three organisations, one of which is an organisation helping women find employment in the professions.

Just a few pages into her argument, she refers to ‘Marriage, the one great profession open to our class from the dawn of time to the year 1919’1. When discussing the right of women to earn a living (and Woolf is concerned here with middle class women, the ‘daughters of educated men’) she refers to ‘an Act which unbarred the professions. The door of the private house was thrown open’.2) She comes back to the date 1919 again and again, using it as a talisman. Of course, Woolf was writing literature, not history, and the repeated use of ‘1919’ is a device she was using to increase her historical authority and structure her argument.

Nevertheless, this device would not have worked if 1919 had meant nothing to her audience. Clearly it did resonate on some level to Woolf's reading public in 1938.

And yet, historians assessing the significance of 1919 since then do not see the year as sacred at all.

So what did this Act that Woolf prized so highly actually do? The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 begins:

A person shall not be disqualified by sex or marriage from the exercise of any public function, or from being appointed to or holding any civil or judicial post, or from entering or assuming or carrying on any civil profession or vocation.3

The effect of this was to enable women to enter professions such as law and accountancy and to be jurors and magistrates for the first time. It also went some way to allowing women to enter the higher ranks of the civil service. The historian Martin Pugh calls the Act ‘a broken reed in the face of the resurrection of obstacles such as the bar on married women and further protective legislation.'4 Alison Oram in her study of women teachers says that the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act ‘simply freed the employer from any restrictions, but gave no rights to the employee.’5 And it is true that the Act was an enabling one; it allowed the appointment and holding of posts, but did not affect the employer’s ability to dismiss women.

But the question should then be asked; if the Act was such a dead letter, why was it passed at all? What did the members of the House of Commons and House of Lords think they were doing? And did contemporary feminist campaigners share these critical assessments?

This paper will examine the intentions of Parliament, government, the civil service and pressure groups during the Parliamentary passage of the Act. By tracing its passage through the House of Commons and House of Lords using Parliamentary Debates, government records and the papers of MPs and women's organisations, this paper will argue that the negative judgment of historians overlooks the positive intentions of many at the time; that the act was a considerable achievement for the circumstances in 1919; that it provided some valuable changes in the law for women; and that although government and the civil service can be shown to have restricted the reform, Parliament did not.

Some of the negative opinion about the Act stems from the fact that it was not the first choice bill of the House of Commons. It was a government bill introduced to kill off a more radical private members’ bill. The Women’s Emancipation Bill was introduced by the Labour Party on 21 March 1919, ‘To remove certain restraints and disabilities imposed on women’.6 This bill contained three clauses: to remove the disqualification of women for holding civil and judicial appointments; to include women on the franchise on the same terms as men; and to allow women to sit and vote in the House of Lords. This came a year after the Representation of the People Act 1918, which gave the Parliamentary franchise to all men and to women who were over the age of 30 and met certain property qualifications; and the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918, which allowed women to become MPs. Entry to professions, equal franchise and entry to the Lords were natural goals to follow on.

The Women’s Emancipation Bill was high on the agenda of the Labour Party; they used their second place in the private members' bill ballot for it.7 It successfully passed all stages in the House of Commons including a division at third reading against whipped government opposition. lt had its second reading debate on 4 April 1919. Twenty-seven MPs spoke over sixty-seven columns of debate, and the tone is remarkably sympathetic. The few who opposed the Bill argued mainly against equal franchise, not the civil and judicial appointments. Various MPs cited from their own experience. Several stated that they themselves were magistrates or lawyers, and particularly supported the idea of women in these roles. Others testified to the suitability of women in public life from their experience on public boards, and even in politics. Captain Loseby, a schoolmaster and barrister, cited the example of his six ‘shabby genteel’ sisters who had the options only of being governesses, nurses, or schoolmistresses, which were honourable but ‘underpaid, overworked and ill-fed professions… all other avenues were closed’.8

What this shows is that the concept of women becoming lawyers and magistrates was no longer controversial. A small number of dedicated women had been campaigning to enter the legal profession since the 1870s, studying law degrees and agitating to practice. These included Bertha Cave, Christabel Pankhurst and Ivy Williams, who unsuccessfully applied to join the Bar in 1903. It culminated in the case of Gwyneth Bebb versus the Law Society in 1913,9 which stated that women could not be solicitors because they never had been solicitors, and Parliamentary legislation was required to change this. Several efforts to introduce legislation failed between 1913 and 1918, but the effects of war and the achievement of the franchise for some women changed attitudes, and in March 1919 a Barristers and Solicitors (Qualification of Women) Bill passed the Lords with almost no opposition.10 Similarly, a Justices of the Peace (Qualification of Women) Bill passed the Lords later in the year, 11 and in both cases the Lord Chancellor gave government support.12 Both these bills were rendered unnecessary by the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act.

Labour MPs were particularly keen to stress that the introduction of the bill by the Labour party was ‘simply the natural sequence of all our past work and past efforts’.13 In contrast to many lawyers in the ranks of the Liberals and Conservatives, virtually all of the Labour MPs who spoke in strong support came from a mining background. Miners were not known for feminist sympathies, yet here they were, introducing a bill to allow middle-class women to become lawyers and accountants. The Labour Party’s election manifesto in 1918 had included a statement that ‘the Labour Party is the Women’s Party,’14 and by introducing the Women’s Emancipation bill early in the new Parliament Labour were able to use this as a demonstration of their good will, stealing a march on the government.

The Women’s Emancipation Bill passed resoundingly on second reading in the House of Commons with 119 votes to 32.15 This was a major triumph for a private members’ bill, and a narrow victory in that a private members bill had to get 100 votes in favour to avoid closure.16 Ray Strachey states in her classic history of the feminist movement The Cause that ‘The Government… resisted this Bill, but the Members of the House of Commons hardly dared to vote against it, not knowing what their female constituents might have to say.’17 The Bill then passed without amendment at committee stage on 14 May .

Two days later, the Women’s Emancipation Bill finally made it onto the government agenda. It was discussed in the war cabinet committee of home affairs on 16 and 28 May as the government pondered what to do at the approaching third reading. Here the civil service showed its hand, expressing two major concerns, firstly about women working after marriage and secondly about the possibility of women serving overseas. The cabinet committee concluded that they should draft a completely new bill taking account of these objections.18 There was also no appetite for legislating for equal franchise: it was seen as too soon, in the first session of the first Parliament after the last franchise extension.

So at the third reading of the Women’s Emancipation Bill on 4 July the government finally weighed in against it – saying they would introduce their own bill. Nineteen MPs spoke over seventy-three columns of debate and the speeches were almost entirely in favour of the Women’s Emancipation Bill as it stood. Women’s organisations, previously caught by surprise at Labour’s introduction of this bill, had by now rallied to lobby sympathetic MPs.

Among them was Lord Robert Cecil, who in an impressive detailed penultimate speech, systematically destroyed all arguments against the bill, ridiculed the government’s position and brought everything back to the fundamental points the bill was trying to address.19 Cecil must have cut an influential figure, as a son of the former prime minister Lord Salisbury, a lawyer and a government minister during the First World War.20 As a supporter of women in the law, he had also represented Gwyneth Bebb in the Court of Appeal. The result was an unusual victory for a private members’ bill in the face of government hostility.21 In the following division the government was defeated 100 to 85, amid calls of ‘Resign, resign!’22

Although the Women’s Emancipation Bill had successfully passed all its hurdles in the Commons, it now moved on to the Lords; and by now the government had come up with its own bill, the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Bill. This had its second reading on 22 July and the introductory speech by the lord chancellor, Lord Birkenhead, left peers in no doubt that this bill was intended to kill off the Women’s Emancipation Bill, which he systematically rubbished. Lord Kimberley, who was due shortly to introduce the Women’s Emancipation Bill in the Lords, was taken by surprise, saying ‘I was not in the least prepared to hear my “baby” – my Bill – torn to pieces by the noble and learned Lord on the Woolsack tonight.’23 Lord Birkenhead was notorious for his personal antagonism to women’s causes, but in this case, as the government had failed to block it in the Commons, it simply fell to him as the government representative in the Lords to do the job.

The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Bill, as presented to the House of Lords and discussed in second reading on 22 July, consisted of the following two clauses: Clause 1 – a person would not be disqualified by sex [marriage was not mentioned] from exercising any public function, or serving on juries, with two provisos:

Proviso (a) - regulations might be made prescribing the mode of admission to the civil service, and excluding women from certain branches;

Proviso (b) - judges might exempt women from jury service by reason of nature of evidence or issues.

Clause 2 – allowed peeresses in their own right to sit in the House of Lords.

Before this bill appeared before Parliament, various drafts had been made by the lord chancellor’s office and considered in the war cabinet committee of home affairs. One important addition during drafting was the specific mention of juries.

Edward Shortt (home secretary and also a KC) remarked 'he did not like the idea, but if women were going to be judges there was no reason why they should not sit on juries'.24

The Lord Chancellor anticipated that peers would find the bill ‘surprising, and to many extremely disagreeable’, though in fact the peers who spoke were generally in favour of allowing women entry to the professions, and most of the debate focussed on peeresses. The peeresses clause was dropped at committee stage without a division.25 Apart from that, the Lord Chancellor drove the bill through the Lords in the form the government wished. The fact that he himself clearly disliked it was nothing new; he had bitterly opposed women’s suffrage before the war but as attorney general in 1918 he had had to pilot the Representation of the People bill through the Commons.

Now that the Women’s Emancipation Bill was dead, the attention of women lobbyists and the peers and MPs sympathetic to them switched to attempts to amend the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Bill to make it as acceptable as possible. Some amendments were relatively straightforward and successful, for example the inclusion of a phrase to ensure the admittance of women to incorporated professional societies, which was the result of lobbying by the Society of Accountants and the Faculty of Actuaries in Edinburgh,26 and was added to bill at committee stage in the Lords. This was a good victory for the pressure groups and made a real difference to some individual women. Of course the wording ‘incorporated professional societies’ did not cover all the organisations it might, for example private clubs. Draftsman Hugh Godley remarked in a letter that the word ‘incorporated’ was ‘necessary to avoid admitting women to the Athenaeum!’27 But no wording could be found to prevent this; regulation of private clubs is still controversial today, and women were not admitted as members to the Athenaeum until 2002.

The bill moved on to the House of Commons with its second reading on 14 August 1919. There was no debate, and women’s organisations were actually worried at this point that the bill might be abandoned altogether.

However it was not shelved, and next came for detailed consideration in the Commons at committee stage on 27 October. Again, some amendments were made with little controversy and almost no debate, such as a new Clause 2, allowing women to qualify as solicitors in three years rather than five if they already possessed a university degree or equivalent (an exemption which already applied to men, thus putting women on the same footing). Another new addition was Clause 3 stating that universities had the power to admit women to membership or degrees. As a direct result of this, Oxford chose to admit women to degrees within a year, though Cambridge did not do so until 1948.

There was more debate on other issues including the marriage bar, proviso (a), mixed juries and women peers. One symbolically important amendment was introduced by Major Hills so the bill began ‘A person shall not be disqualified by sex or marriage’. This point was resurrected from the Women’s Emancipation Bill, and it was clear from the debate that Hills’s intention was to remove the marriage bar.

Although it was accepted, it was to no avail; the continuing existence of the marriage bar remained a thorn in the side of women’s organisations until after the Second World War. In the civil service and elsewhere it remained the norm for women to resign on marriage, and the bar was introduced for the first time in teaching. There was some success in removing the bar at regional level,28 but attempts at national level to cite the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act in court cases failed.29 This was a major criticism of the act by some feminist organisations such as the Six Point Group, and remains so by historians. Yet it is difficult to see what else could have been done in 1919. Neither the Women’s Emancipation Bill nor the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Bill were drafted in terms of explicitly giving married women the right to work.

Another proposed amendment was introduced by Samuel Hoare to alter proviso (a). This failed; the amendment was lost 189 to 101. A number of orders in council were duly made in 1920-21 which confirmed the fears of women’s organisations, on the mode of admission and the conditions of the civil service,30 and reserving to men posts in the diplomatic consular services, the colonies and protectorates. The battle for women’s equality within the civil service went on throughout and beyond the inter-war period. As Meta Zimmeck has shown, the weight given to the claims of ex-servicemen, combined with the marriage bar, reservation of posts, mechanisms of recruitment, and reorganisation of grades, all worked to limit the opportunities for women.31 Equal pay was not achieved until 1954.

Nevertheless women did enter the higher ranks for the first time.32 It is true that numbers remained small – 43 women were in the administrative grade in 1939, 3% of the total. But women’s participation in the civil service overall remained steady; the administrative class was a small class, which Zimmeck has compared to a gentleman’s club.33 It was always going to take time for women to enter such a club in significant numbers.

Another proposed amendment to the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Bill which did not succeed was to leave out the proviso (b) that there could be single sex juries. This was withdrawn after the Commons were assured that ‘In the ordinary course [juries] should be mixed’.34 The rules under which women were to become jurors35 were drafted after the act was passed. Claud Schuster (permanent secretary to the Lord Chancellor) explained in a letter that the job had been done with great difficulty as 'the Judges did not like either the Rules or the Act'.36 The rules, issued on 12 July 1920, included allowing single-sex juries. This was opposed by women’s organisations from the start.37 A judge’s discretionary right to exclude women from juries remained an issue for a long time, and women did not serve on juries on the same terms as men until 1974.

The Commons also amended the bill to include the right of peeresses to sit in the House of Lords, but this was removed by the Lords.38 Time was very short now and the whole bill could have been lost if the Commons had chosen to press this point. As it was, the bill received royal assent on 23 December 1919, the last day of the parliamentary session.39

So what did women’s organisations make of it at the time? It is of course true that feminist groups enthusiastically supported the Women’s Emancipation Bill and would have preferred it over the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Bill.40

Nevertheless it is misleading to argue that the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Bill was ‘opposed’ by such groups. They did work vigorously to amend it, and this should be viewed not as a negative action but as positive constructive lobbying work; part of the process of agreeing parliamentary legislation; realistic work towards achievable goals. Of course it was extremely disappointing to women’s groups that the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act omitted the equal franchise clause. However they did not seriously expect the extension of the vote on equal terms so soon.41 Millicent Fawcett wrote that 1919 was ‘not a bad harvest for one session when we remember the 12 years‘ work necessary to get the Midwives Bill 1902, or the 32 years of hard labour before the Nurses Registration bill’. Fawcett was positive regarding women on juries, as magistrates, in universities and the legal profession, though the civil service situation was ‘disappointing’.42

In conclusion. A century on, should we be recognising 1919 as the 'sacred year' Virginia Woolf claimed it to be?

The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act was a government replacement for a more radical private members’ bill, and as such it was a compromise. The two really radical clauses on the franchise and woman peers were lost. The act has been consistently cited by historians as evidence in a wider historical judgement that feminist achievements in the inter-war period were insignificant; that the reforms which were achieved were ‘guided by non-feminist forces’ and therefore channelled women into maintaining their more traditional place in society.43

However, this negative verdict obscures the positive spirit that the Women’s Emancipation bill was passed in, it overlooks the genuine achievements of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act, and assumes standards that fail to take into account the situation in 1919. The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act was passed only a year after the end of the Great War, with the peace settlement ongoing, trouble in Ireland, returning soldiers - the government had very many other priorities and it is surely remarkable that such a bill was able to progress at all. It was only a year after women had been given the limited franchise, only a few years after suffragettes had been barracking Parliament; it was only now that women in Parliament were voters and MPs, and not potential trouble-makers capable of violence.

And although the government and the civil service have been shown to have limited the extent of the reform achieved, there was considerable support in parliament for more radical reform. Careful consideration of the debates show real attempts by both peers and MPs, firstly to try and get the Women’s Emancipation Bill through, and secondly to make the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Bill work. In particular the support from men of diverse backgrounds is striking.

Finally, even in its revised form, the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act really was a significant advance on the previous situation. Women were now allowed into the professions and into professional bodies, whereas before 1919 the only profession to have any significant numbers of women was medicine.44 Women were allowed to become barristers, solicitors, magistrates, sit on juries. Sympathetic MPs did as much as they could to mitigate the effect of regulations which would hamper women, although as Major Hills concluded, ‘We shall not carry the citadel at the first assault, I fear’.45

1918, the year of the partial franchise, was hugely significant both in terms of principle and practice. But 1919 was the year when finally having put the long- running battle for the vote to one side, feminist organisations were able to move on to other issues. Entry to the professions, or (as Woolf put it) 'the right of middle-class women to earn their own living', was the first but by no means the only achievement, as a host of other legislation affecting women's lives and gender equality was passed in the inter-war period. Thanks to efforts by feminist organisations, work by women MPs, and the influence of women voters, legislation passed between 1918 and 1939 equalized property inheritance rights; improved training for nurses and midwives; reformed the marriage and divorce laws; removed the automatic death penalty for infanticide and created the offence of child destruction; raised the age of consent and the age of marriage to 16; introduced equal guardianship, and widows and orphans pensions; regulated the sale of drink to children, and reformed legitimacy law and adoption law, as well as achieving Equal Franchise.

One hundred years on, it is right that we remember what happened in Parliament a century ago and celebrate it accordingly.

Dr Mari Takayanagi

Senior Archivist, Parliamentary Archives

Detailsnavigate_next

Dr Mari Takayanagi

Senior Archivist, Parliamentary Archives

Dr Mari Takayanagi

Senior Archivist, Parliamentary Archives

Detailsnavigate_next

Dr Mari Takayanagi

Senior Archivist, Parliamentary Archives

Dr Mari Takayanagi

Senior Archivist, Parliamentary Archives

Detailsnavigate_next

Dr Mari Takayanagi

Senior Archivist, Parliamentary Archives

Footnotes

1 Virginia Woolf, A room of one's own ; Three guineas (London, Penguin, 1993), p.120.

2 Ibid, p. 130.

3 Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act, ch. 71, 1919.

4 Martin Pugh, Women and the women's movement in Britain, 1914-1999 (Basingstoke, 2000), p. 90.

5 Alison Oram, Women teachers and feminist politics, 1900-39 (Manchester, 1996), p. 163.

6 HC Bill 38, II.1187 (1919).

7 Times, 9 April 1919.

8 HC Deb, 4 Apr. 1919 vol. 114, c. 1605-6, Captain Loseby.

9 Rosemary Auchmuty, 'Whatever happened to Miss Bebb? Bebb v The Law Society and women’s legal history', Legal Studies: The Journal of the Society of Legal Scholars, (2011) 31 (2), pp. 175-343.

10 HL Deb, 11 Mar. 1919 vol. 33 c. 591, Lord Buckmaster.

11 HL Deb, 20 May 1919 vol. 34 c. 736, Earl Beauchamp.

12 HL Deb, 11 Mar. 1919 vol. 33 c. 596; HL Deb, 20 May 1919 vol. 34, c. 738-9, Lord Chancellor.

13 HC Deb, 4 Apr. 1919 vol. 114 c. 1561, Adamson.

14 F.W.S Craig, British General Election Manifestos 1918-1966 (Chichester, 1970), p. 6.

15 HC Deb, 4 Apr. 1919 vol. 114 c. 1625-8.

16 Peter Alexander Bromhead, Private members' bills in the British parliament (1956), p. 105.

17 Ray Strachey, "The Cause": a short history of the women's movement in Great Britain (1928, reprinted London, Virago, 1978).

18 TNA, CAB 26/1, HAC 28 16/5/19 item 6 & HAC 30 28/5/19 item 4.

19 HC Deb, 4 July 1919 vol. 117 c. 1340, Lord Robert Cecil.

20 Martin Ceadel, ‘Cecil, Edgar Algernon Robert Gascoyne- [Lord Robert Cecil], Viscount Cecil of Chelwood (1864–1958)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford, 2004.

21 Bromhead, Private Members' Bills, p. 105.

22 HC Deb, 4 July 1919 vol. 117 c. 1345.

23 HL Deb, 22 July 1919 vol. 35 c. 892, Lord Chancellor; c. 901 & 903, Lord Kimberley.

24 TNA, CAB 26/1, HAC 32 26/6/19 item 4.

25 Duncan Sutherland, 'Peeresses, parliament, and prejudice: the admission of women to the House of Lords, 1918-1963', Parliaments, Estates and Representation, 20 (2000).

26 TNA, LCO 2/439. Letter from James Watt, 21 July 1919.

27 TNA, LCO 2/439. 25 July 1919.

28 Oram, Women teachers, p. 167, 170-171.

29 Susan Atkins and Brenda M. Hoggett, Women and the law (Oxford, 1984), p. 17.

30 London Gazette 3 Aug. 1920 pp. 8082-3.

31 Zimmeck, 'Strategies and stratagems for the employment of women in the British Civil Service, 1919-1939', Historical Journal, 27 (1984).

32 TNA, T 162/550, file 3754/05/1 & 2.

33 Zimmeck, 'Strategies and stratagems,' pp. 921-2, 916, 905.

34 HC Deb, 27 Oct. 1919 vol 120 c. 383, Major Hills; c. 384-5, E. Hume-Williams; c. 387, Captain Elliot; c.

38 9, solicitor general.

35 Stat Rules & Orders 1920 no 1978 L.51.

36 TNA, LCO 2/559.

37 Women’s Library, 2NSE/C/02, p. 21.

38 HC Deb, 27 Oct. 1919 vol. 120 c. 853-4; HL Deb, 11 Nov. 1919 vol 37 c. 181.

39 Journal of the House of Commons 1919, p.428.

40 Women’s Library, 2LSW/A/4/1/3/2, minutes 9 July 1919.

41 Strachey, The Cause, p. 376.

42 Millicent Garrett Fawcett, The women's victory -- and after: personal reminiscences, 1911-1918 (London, 1920), pp. 163-4.

43 Harold Smith, 'British feminism in the 1920s', British Feminism in the Twentieth Century (Aldershot, 1990).

44 Ellen Jordan, The women's movement and women's employment in nineteenth century Britain (London, 1999), pp. 219-221.

45 Women’s Library, 6APC/2/06. Hills to Miss Caldcleugh, 10 Nov 1919.